Maybe the art proposal itself could be the artwork.

We write and propose and speculate. We try to talk about the thing we want to make if maybe somehow we could have the funding. Or, we propose something close to what we would like to do but fits all the standards and requirements of a project scope. We’re trying to make the thing fit.

We’re frustrated and confused, but hopeful.

There’s advice online and in books on how to write the right proposal. There are educational sessions and Q and A’s on how to make your art proposal “successful.” But it all starts to seem a little repetitive–trying to make an amorphous thing fit into a tight box.

What are we doing?

Making artwork isn’t about compromises and fitting into a format. All practicing artists seem to know this at some point. Yet somehow, we’ve become more docile and corporate-minded–thinking that if we can just “sell” our idea, that it will come to fruition. And it’s not the selling that is the problem. We all need to live and earn money for us and our families. But why are we accepting that we should cater the nature of our work to fit within the parameters that an institution or organization puts forth?

Proposing absurd reality

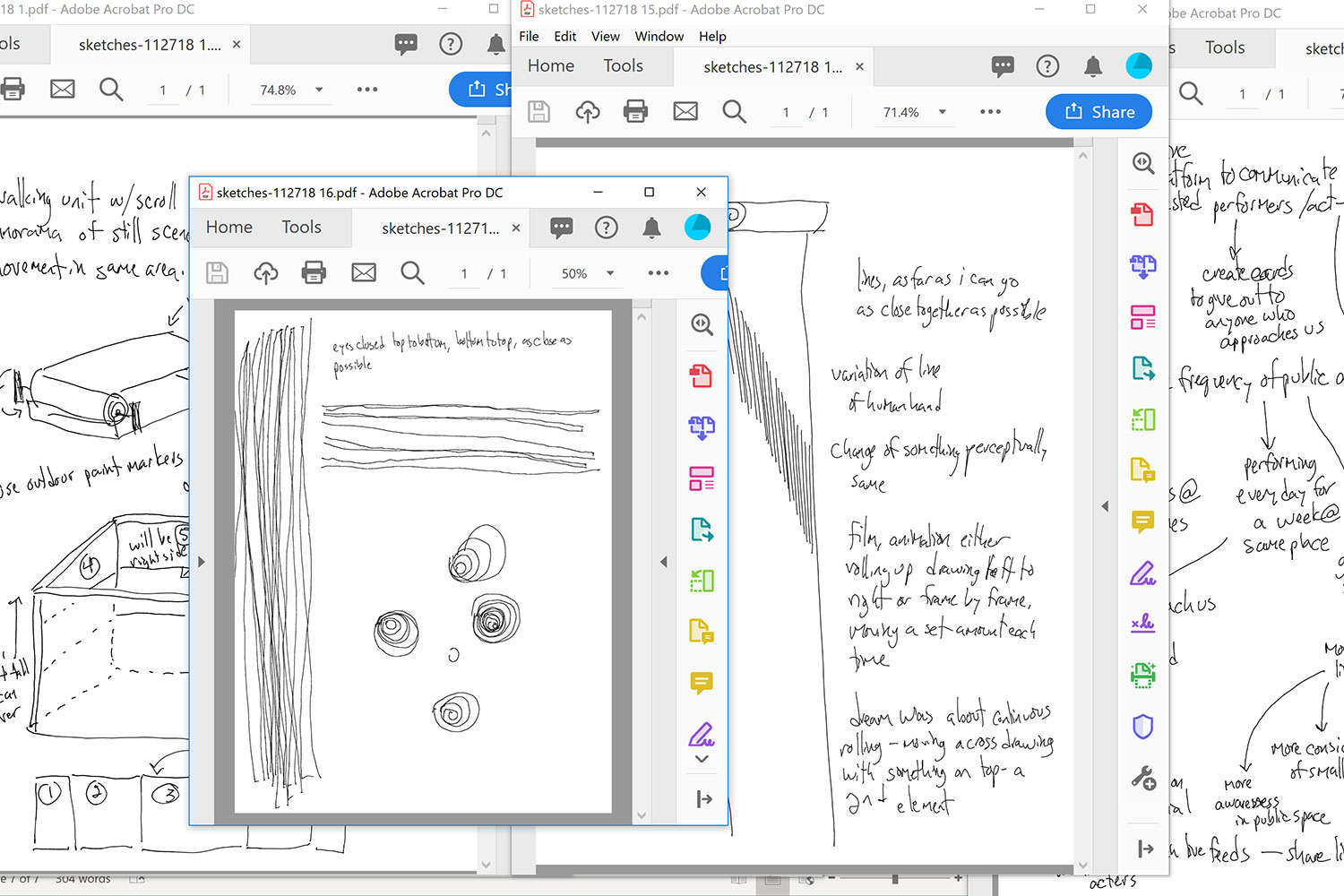

Propose something that you think they would never accept. Write an art proposal of something absurdly accurate to what you actually want to create. The percentage likelihood of being accepted for a grant, public art project, fellowship or any other opportunity can be pretty slim. So don’t make it fit. Make it clear. Make it well-written. Make it accurately outlined in all its steps (even the fuzzy ones…allow for unclear steps). But make it perfectly and wonderfully unique and without the estimated trappings of the institution asking for an artist’s involvement. Do we want to be designers of an artistic reality or do we actually want to be artists? With more proposals coming in to the mix of this nature, institutions might have to face whether they want to hire artists to make artwork or whether they want a designer for an event or experience.

You’re an artist! Don’t dilute your politics or your intent or your love of the most obscure. As long as we continue to submit art proposals that speak only to the requirements asked of it, as works to “engage the public,” “have a community element,” “be made of durable materials,” or “apply an aesthetic,” we’re just art-ing AT things.

By putting an alternative in front of someone, you present them with the possibility that things can be different than what they are. And they should be different. Life is short and it way too easily can become predictable and boring.